The Abolitionists in Pennsylvania

Founding of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society (PAS)

As early as 1688, four German Quakers in Germantown near Philadelphia protested slavery in a resolution that condemned the “traffic of Men-body.” By the 1770s, abolitionism was a full-scale movement in Pennsylvania. Led by such Quaker activists as Anthony Benezet and John Woolman, many Philadelphia slaveholders of all denominations had begun bowing to pressure to emancipate their slaves on religious, moral, and economic grounds.

In April 1775, Benezet called the first meeting of the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully held in Bondagevii at the Rising Sun Tavern. Thomas Paineviii was among the ten white Philadelphians who attended; seven of the group were Quakers. Often referred to as the Abolition Society, the group focused on intervention in the cases of blacks and Indians who claimed to have been illegally enslaved. Of the twenty-four men who attended the four meetings held before the Society disbanded, seventeen were Quakers.

Six of these original members were among the largely Quaker group of eighteen Philadelphians that reorganized in February 1784 as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondageix (commonly referred to as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, or PAS). Although still occupied with litigation on behalf of blacks who were illegally enslaved under existing laws, the new name reflected the Society’s growing emphasis on abolition as a goal. Within two years, the group had grown to 82 members and inspired the establishment of anti-slavery organizations in other cities.

PAS reorganized once again in 1787. While previously, artisans and shopkeepers had been the core of the organization, PAS broadened its membership to include such prominent figures as Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush, who helped write the Society’s new constitution. PAS became much more aggressive in its strategy of litigation on behalf of free blacks, and attempted to work more closely with the Free African Society in a wide range of social, political and educational activity

In 1787, PAS organized local efforts to support the crusade to ban the international slave trade and petitioned the Constitutional Convention to institute a ban. The following year, in collaboration with the Society of Friends, PAS successfully petitioned the Pennsylvania legislature to amend the gradual abolition act of 1780. As a result of the 2000-signature petition and other lobbying efforts, the legislature prohibited the transportation of slave children or pregnant women out of Pennsyvania, as well as the building, outfitting or sending of slave ships from Philadelphia. The amended act imposed heavier fines for slave kidnapping, and made it illegal to separate slave families by more than ten miles.

Despite its unwavering support of the black community, PAS revealed its uncertain feelings toward freed slaves in a 1789 broadside entitled Address to the Public, in which they wrote of the devastating effects of slavery, effects which they said often left blacks unable to function as full citizens. Although intended to be sympathetic, the PAS statement gave support to existing prejudices, and no doubt would have been refuted by PAS founder Anthony Benezet, who, before his death in 1784, wrote numerous pamphlets in which he challenged the notion of black inferiority.

In 1789, under its new president, Benjamin Franklin, PAS announced a plan to help free black people better their situation. In conjunction with the Free African Society, PAS attempted to create black schools, help free blacks obtain employment, and conduct house visits to foster morality and a strong work ethic in Philadelphia’s black residents. PAS’s Committee of Guardians, established in 1790, facilitated the placement of black children in indentures (a common practice of the time among Philadelphia’s free blacks), monitored the conditions under which the children lived, and intervened with legal and material support when necessary.

In 1815, PAS supported Richard Allen of the Bethel Church in their successful legal battle against takeover by the white Methodist leadership. PAS was listed along with Allen in the certificate that formally transferred ownership of the property on which Bethel stood.

In the decade after the War of 1812, such factors as the post-war economic slump, the death of Rush and other leaders, and a decline in support for abolition by Philadelphia’s elite led to increasing anti-black sentiment and the legal, physical, and emotional harassment and exclusion of black citizens. By December 1833, when the American Anti-Slavery Society was founded in Philadelphia, PAS had become a small, embattled group with little public support.

Ref.: http://www.paabolition.org/

Pennsylvania Hall

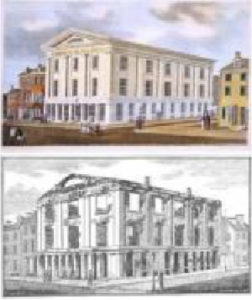

A grand structure that was once called “one of the most commodious and splendid buildings in the city,” Pennsylvania Hall was constructed to provide a forum for discussing “the evils of slavery,” as well as other matters “not of an immoral character.” The building was opened on the morning of May 14, 1838 — a Monday. On Thursday evening, after four days of dedication ceremonies and abolition-related meetings, the building was burned to the ground by an angry mob.

It was precisely because abolitionists had such a difficult time finding space for their meetings that plans for the Hall were initiated. A joint-stock company was formed to finance the construction. Two thousand people — abolitionists, mechanics and other workers, women, and prominent citizens — bought shares in the company that sold for $20 apiece. Those who could not afford to buy shares donated materials and labor. Forty thousand dollars was raised to construct the building.

On the first floor of Pennsylvania Hall were lecture and committee rooms, as well as a bookstore that sold abolitionist publications. The second and third floors was devoted to a large hall, with galleries on the third floor. Above the stage in the hall was the motto: “Virtue, Liberty and Independence.”

The first event scheduled was a dedication ceremony, during which letters from Gerrit Smith, Theodore Weld, and John Quincy Adams were read. Adams, who had by then already served as president of the United States, summed up the general sentiment of those in the hall: I learnt with great satisfaction. . . that the Pennsylvania Hall Association have erected a large building in your city, wherein liberty and equality of civil rights can be freely discussed, and the evils of slavery fearlessly portrayed. . . . I rejoice that , in the city of Philadelphia, the friends of free discussion have erected a Hall for its unrestrained exercise.

The sentiment outside the building, however, was markedly different. On Tuesday morning notices were found throughout the city. The notices called upon “citizens who entertain a proper respect for the right of property,” and instructed them to “interfere, forcibly if they must, and prevent the violation of these pledges [the preservation of the Constitution of the United States], heretofore held sacred.”

Despite these notices and the growing crowd outside of the hall, the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women met, as scheduled, that morning. On the morning of the following day, men began to gather around the building, “prowling about the doors, examining the gas-pipes, and talking in an ‘incendiary’ manner to groups which they collected around them in the street.” Later in the day they became more unruly, and during the evening’s meeting, while William Lloyd Garrison was introducing Maria W. Chapman to the over 3,000 reformers present, a mob broke into the building, shouting. The mob soon left, only to disrupt the meeting from outside. Rocks came crashing in through the windows while Chapman spoke; the shouting from outside overwhelmed her voice. Angelina Grimké Weld next took the podium. Several times during the meeting the audience rose to leave, only to be persuaded to stay by Weld and other speakers. Undeterred by the loud and disruptive mob, Weld’s speech went on for over an hour. In a display of solidarity and in order to protect the black women, whites and blacks walked out of the hall arm in arm. They were still met by a barrage of insults and rocks.

The mob returned on the following day. Scheduled were more meetings of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, who refused to comply with the Mayor’s request to restrict the meeting to white women only. The building’s managers, fearing that the mob posed a threat, handed the keys over to the mayor. After locking the doors the mayor announced to the crowd that the remaining meetings had been cancelled. The crowd cheered as he walked away. Soon after the crowd broke into the building, destroying the interior and setting fires. The mayor returned with the police, but by now the mob was out of control — any attempts the police made to restore order were met by attacks. By nine o’clock the fires had spread, engulfing the building in flames. Firefighters arrived at the scene but sprayed only the structures that surrounded Pennsylvania Hall. When one unit tried spraying the new building, its men became the target of the other units’ hoses. With no one working to save Pennsylvania Hall, it was soon completely destroyed.

The riotous mob continued to strike over the following days, setting a shelter for black orphans on fire and damaging a black church.

An official report blamed the abolitionists for the riots, claiming that they incited violence by upsetting the citizens of Philadelphia with their views and for encouraging “race mixing.”

|

Credit: (Both images) The Library Company of Philadelphia

Angela Grimké Weld’s speech at Pennsylvania Hall – 1838

Speaking as a southern woman who had seen firsthand the “demoralizing influence” of slavery and its ‘destructiveness to human happiness,” Angela Grimké Weld gave an inspiring speech at Pennsylvania Hall amidst a tumult of rocks thrown through windows and the shouting on an unruly mob.

“What is a mob?’ she asked during the commotion. “What would the breaking of every window be? Any evidence that we arfe wrong, or that slavery is a good and wholesome institution? What if the Mob should burst in among us, break up our meeting and commit violence upon our persons—would this be anything compared to what the slaves endure?”

Men, brethren and fathers — mothers, daughters and sisters, what came ye out for to see? A reed shaken with the wind? Is it curiosity merely, or a deep sympathy with the perishing slave, that has brought this large audience together? [A yell from the mob without the building.] Those voices without ought to awaken and call out our warmest sympathies. Deluded beings! “they know not what they do.” They know not that they are undermining their own rights and their own happiness, temporal and eternal. Do you ask, “what has the North to do with slavery?” Hear it — hear it. Those voices without tell us that the spirit of slavery is here, and has been roused to wrath by our abolition speeches and conventions: for surely liberty would not foam and tear herself with rage, because her friends are multiplied daily, and meetings are held in quick succession to set forth her virtues and extend her peaceful kingdom. This opposition shows that slavery has done its deadliest work in the hearts of our citizens. Do you ask, then, “what has the North to do?” I answer, cast out first the spirit of slavery from your own hearts, and then lend your aid to convert the South. Each one present has a work to do, be his or her situation what it may, however limited their means, or insignificant their supposed influence. The great men of this country will not do this work; the church will never do it. A desire to please the world, to keep the favor of all parties and of all conditions, makes them dumb on this and every other unpopular subject. They have become worldly-wise, and therefore God, in his wisdom, employs them not to carry on his plans of reformation and salvation. He hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise, and the weak to overcome the mighty.

As a Southerner I feel that it is my duty to stand up here to-night and bear testimony against slavery. I have seen it — I have seen it. I know it has horrors that can never be described. I was brought up under its wing: I witnessed for many years its demoralizing influences, and its destructiveness to human happiness. It is admitted by some that the slave is not happy under the worst forms of slavery. But I have never seen a happy slave. I have seen him dance in his chains, it is true; but he was not happy. There is a wide difference between happiness and mirth. Man cannot enjoy the former while his manhood is destroyed, and that part of the being which is necessary to the making, and to the enjoyment of happiness, is completely blotted out. The slaves, however, may be, and sometimes are, mirthful. When hope is extinguished, they say, “let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” [Just then stones were thrown at the windows, — a great noise without, and commotion within.] What is a mob? What would the breaking of every window be? What would the leveling of this Hall be? Any evidence that we are wrong, or that slavery is a good and wholesome institution? What if the mob should now burst in upon us, break up our meeting and commit violence upon our persons — would this be any thing compared with what the slaves endure? No, no: and we do not remember them “as bound with them,” if we shrink in the time of peril, or feel unwilling to sacrifice ourselves, if need be, for their sake. [Great noise.] I thank the Lord that there is yet life left enough to feel the truth, even though it rages at it — that conscience is not so completely seared as to be unmoved by the truth of the living God.

Many persons go to the South for a season, and are hospitably entertained in the parlor and at the table of the slave-holder. They never enter the huts of the slaves; they know nothing of the dark side of the picture, and they return home with praises on their lips of the generous character of those with whom they had tarried. Or if they have witnessed the cruelties of slavery, by remaining silent spectators they have naturally become callous — an insensibility has ensued which prepares them to apologize even for barbarity. Nothing but the corrupting influence of slavery on the hearts of the Northern people can induce them to apologize for it; and much will have been done for the destruction of Southern slavery when we have so reformed the North that no one here will be willing to risk his reputation by advocating or even excusing the holding of men as property. The South know it, and acknowledge that as fast as our principles prevail, the hold of the master must be relaxed. [Another outbreak of mobocratic spirit, and some confusion in the house.]

How wonderfully constituted is the human mind! How it resists, as long as it can, all efforts made to reclaim from error! I feel that all this disturbance is but an evidence that our efforts are the best that could have been adopted, or else the friends of slavery would not care for what we say and do. The South know what we do. I am thankful that they are reached by our efforts. Many times have I wept in the land of my birth, over the system of slavery, I knew of none who sympathized in my feelings — I was unaware that any efforts were made to deliver the oppressed — no voice in the wilderness was heard calling on the people to repent and do works meet for repentance — and my heart sickened within me. Oh, how should I have rejoiced to know that such efforts as these were being made I only wonder that I had such feelings. I wonder when I reflect under what influence I was brought up that my heart is not harder than the nether millstone. But in the midst of temptation I was preserved, and my sympathy grew warmer, and my hatred of slavery more inveterate, until at last I have exiled myself from my native land because I could no longer endure to hear the wailing of the slave. I fled to the land of Penn; for here, thought I, sympathy for the slave will surely be found. But I found it not. The people were kind and hospitable, but the slave had no place in their thoughts. Whenever questions were put to me as to his condition, I felt that they were dictated by an idle curiosity, rather than by that deep feeling which would lead to effort for his rescue. I therefore shut up my grief in my own heart. I remembered that I was a Carolinian, from a state which framed this iniquity by law. I knew that throughout her territory was continual suffering, on the one part, and continual brutality and sin on the other. Every Southern breeze wafted to me the discordant tones of weeping and wailing, shrieks and groans, mingled with prayers and blasphemous curses. I thought there was no hope; that the wicked would go on in his wickedness, until he had destroyed both himself and his country. My heart sunk within me at the abominations in the midst of which I had been born and educated. What will it avail, cried I in bitterness of spirit, to expose to the gaze of strangers the horrors and pollutions of slavery, when there is no ear to hear nor heart to feel and pray for the slave. The language of my soul was, “Oh tell it not in Gath, publish it not in the streets of Askelon.” But how different do I feel now! Animated with hope, nay, with an assurance of the triumph of liberty and good will to man, I will lift up my voice like a trumpet, and show this people their transgression, their sins of omission towards the slave, and what they can do towards affecting Southern mind, and overthrowing Southern oppression.

We may talk of occupying neutral ground, but on this subject, in its present attitude, there is no such thing as neutral ground. He that is not for us is against us, and he that gathereth not with us, scattereth abroad. If you are on what you suppose to be neutral ground, the South look upon you as on the side of the oppressor. And is there one who loves his country willing to give his influence, even indirectly, in favor of slavery — that curse of nations ? God swept Egypt with the besom of destruction, and punished Judea also with a sore punishment, because of slavery. And have we any reason to believe that he is less just now? — or that he will be more favorable to us than to his own “peculiar people?” [Shoutings, stones thrown against the windows, etc.]

There is nothing to be feared from those who would stop our mouths, but they themselves should fear and tremble. The current is even now setting fast against them. If the arm of the North had not caused the Bastille of slavery to totter to its foundation, you would not hear those cries. A few years ago, and the South felt secure, and with a contemptuous sneer asked, “Who are the abolitionists? The abolitionists are nothing?” — Ay, in one sense they were nothing, and they are nothing still. But in this we rejoice, that “God has chosen things that are not to bring to naught things that are.” [Mob again disturbed the meeting.]

We often hear the question asked , What shall we do?” Here is an opportunity for doing something now. Every man and every woman present may do something by showing that we fear not a mob, and, in the midst of threatening’s and reviling’s, by opening our mouths for the dumb and pleading the cause of those who are ready to perish.

To work as we should in this cause, we must know what Slavery is. Let me urge you then to buy the books which have been written on this subject and read them, and then lend them to your neighbors. Give your money no longer for things which pander to pride and lust, but aid in scattering “the living coals of truth” upon the naked heart of this nation, — in circulating appeals to the sympathies of Christians in behalf of the outraged and suffering slave. But, it is said by some, our “books and papers do not speak the truth.” Why, then, do they not contradict what we say? They cannot. Moreover the South has entreated, nay commanded us to be silent; and what greater evidence of the truth of our publications could be desired?

Women of Philadelphia! Allow me as a Southern woman, with much attachment to the land of my birth, to entreat you to come up to this work. Especially let me urge you to petition. Men may settle this and other questions at the ballot-box, but you have no such right; it is only through petitions that you can reach the Legislature. It is therefore peculiarly your duty to petition. Do you say, “It does no good?” The South already turns pale at the number sent. They have read the reports of the proceedings of Congress, and there have seen that among other petitions were very many from the women of the North on the subject of slavery. This fact has called the attention of the South to the subject. How could we expect to have done more as yet? Men who hold the rod over slaves, rule in the councils of the nation: and they deny our right to petition and to remonstrate against abuses of our sex and of our kind. We have these rights, however, from our God. Only let us exercise them: and though often turned away unanswered, let us remember the influence of importunity upon the unjust judge, and act accordingly. The fact that the South look with jealousy upon our measures shows that they are effectual. There is, therefore, no cause for doubting or despair, but rather for rejoicing.

It was remarked in England that women did much to abolish Slavery in her colonies. Nor are they now idle. Numerous petitions from them have recently been presented to the Queen, to abolish the apprenticeship with its cruelties nearly equal to those of the system whose place it supplies. One petition two miles and a quarter long has been presented. And do you think these labors will be in vain ? Let the history of the past answer. When the women of these States send up to Congress such a petition, our legislators will arise as did those of England, and say, “When all the maids and matrons of the land are knocking at our doors we must legislate.” Let the zeal and love, the faith and works of our English sisters quicken ours — that while the slaves continue to suffer, and when they shout deliverance, we may feel the satisfaction of having done what we could.

Ref.: History of Pennsylvania Hall which was Destroyed by a Mob on the 17th of May, 1838

Negro Universities Press, A Division of Greenwood Publishing Corp,

New York, 1969

|

|

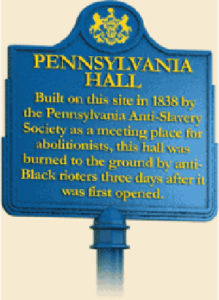

Today, a state historical marker stands at the original location, on 6th Street immediately south of Race Street in Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania Abolition Society

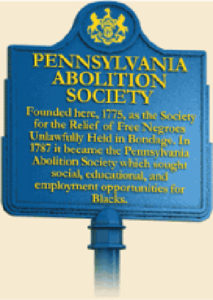

Marker Location: Front Street below Chestnut Street, Philadelphia

Marker Text

Founded here, 1775, as the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. In 1787 it became the Pennsylvania Abolition Society which sought social, educational, and employment opportunities for Blacks.

Behind the Marker

Legendary abolitionist Anthony Benezet organized the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage in April 1775. Its first meeting was held at the Rising Sun Tavern in Philadelphia in order to help a mixed-race woman named Dinah Nevill and her three children. Nevill, who claimed to be free, was threatened with being sold into slavery in Virginia. Benezet’s small group of ten local white residents fought unsuccessfully to prevent her sale but ultimately managed to arrange for her family’s freedom and return to Philadelphia.

The Executive Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, c. 1851, included (seated, right to left) James Mott, Lucretia Mott, and Robert Purvis.

Credit: Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College

The group stopped holding regular meetings but reorganized in 1784, the year Benezet died, in order to help black families establish their freedom under the new Pennsylvania Abolition Act (1780). George Washington wrote a letter in 1786 criticizing the group’s activities because a fellow Virginia slaveholder had been forced to travel to Philadelphia to deal with “a vexatious lawsuit respecting a slave of his, which a Society of Quakers in the city (formed for such purposes) have attempted to liberate.” The future president claimed that he desired the abolition of slavery himself, but thought the best way to accomplish the goal was through the legislative process.

Without even realizing it, the organization then followed Washington’s advice. In 1787, the members drew up a new governing document and elected Benjamin Franklin, a former slave owner, as their president. They began to spend much of their time lobbying for state and federal legislation against slavery. They also started providing assistance to the free blacks of Philadelphia, funding schools and helping formers slaves adjust to freedom.

What the Society did not pursue, however, was racial integration. For many years, the Pennsylvania Abolition Society remained almost exclusively white. Other antislavery societies that accepted black members soon overshadowed it and contributed more to he ultimate destruction of slavery

The Timeline of Abolitionism in Pennsylvania 1830 – 1860