Activities at Camp William Penn

“This is our golden moment. The Government of the United States calls for every able-bodied colored man to enter the army for three years’ service, and join in fighting the battles of Liberty and the Union. A new era is open to us. For generations we have suffered under the horrors of slavery outrage and wrong! Our manhood has been denied, our citizenship blotted out, our souls seared and burned, our spirits cowed and crushed, and the hopes of the future of our race involved in doubt and darkness. But now the whole aspect of our relations with the white race is changed.

“If we love our country, if we love our families, our children, our homes, we must strike now while the country calls. More than a million white men have left comfortable homes and joined the armies of the Union to save their country. Cannot we leave ours and swell the hosts of the Union, save our liberties, vindicate our manhood and deserve well of our country?

“Men of color! Brothers and Fathers! We appeal to you! By all your concern for yourselves and your liberties, by all your regard for God and humanity, by all your desire for citizenship and equality before the law, by all your love of country, to stop at no subterfuges, listen to nothing that shall deter you from rallying for the army. Strike now and you are henceforth and forever Freemen!”

It was the summer of 1863. The war between the states, the Civil War, was in its third year. The Emancipation Proclamation had become effective on January 1. And for the first time in American history, Negroes were being permitted, indeed requested, to serve in the United States Army. Prominent Black leaders in the North promptly instituted a campaign encouraging members of their race to enlist, using stimulating messages like the one above which appeared in Philadelphia in June, 1863.

Nearly a year had passed since Congress had enacted, on July 17, 1862, a bill authorizing the President ”to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of the rebellion.” President Lincoln did not immediately avail himself of this authority; nor did Congress take any action on a bill introduced in February 1863, by Rep. Charles Sumner, which provided for the enlistment of 300,000 colored troops.

The first serious move in the North was made by the state of Massachusetts, which established, early in 1863, “the 54th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Colored.” This organization, which was heavily populated with men from Pennsylvania, went on to acquire unusual fame and distinction.

Meetings were subsequently held in Philadelphia to plan the formation of similar state regiments. However, the first move was made, not by the State of Pennsylvania, but by the Federal Government. In June, 1863, Lieutenant Charles C. Ruff, the United States Army mustering officer in Philadelphia, announced that he had received orders to “authorize the formation of one regiment of ten companies, colored troops, each company to be eighty strong, to be mustered into the United States service and provided for, in all respects, the same as white troops.

Within a week, to accommodate and train the new recruits, Camp William Penn was established directly north of the city limits, in Cheltenham Township, Montgomery County. The site chosen for the camp was at Washington Lane and Church Road, on the property of Civil War financier Jay Cooke. This location was especially well selected, not only because the recently constructed North Penn Railroad provided easy access to Philadelphia, but also because many of the neighboring residents were Quakers. Among the Quakers of Cheltenham Township, an uncommon sympathy for the Negro cause prevailed, as evidenced by their fervent opposition to slavery, first publicly expressed in 1698, and their participation in the activities of the Underground Railroad.

Camp William Penn became the first recruiting and training center for Black soldiers to be operated by the United States Government. To assure its success, not only was the location carefully chosen, but extreme care was taken as well in the selection of officers. Lieutenant Colonel Louis Wagner of the 88th Regiment Pennsylvania Infantry, a German- born volunteer, who had been badly wounded at Bull Run, was named camp commander at his own request. Subordinate officers, chosen mostly from regiments of white troops in the field, received special training at a school of instruction at 1210 Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, which was operated by the “committee for the supervision of recruiting of colored troops.”

This new venture immediately attracted the interest and support of prominent citizens, both black and white. The recently organized Union League of Philadelphia raised $34,000 within a few days to outfit and equip the new regiments. Many prominent Negro leaders, including William Still, visited the camp to examine the facilities.

The first recruits arrived at Camp William Penn on July 4, 1863. Between that time and August 31, 1864, a total of 10,940 men, in 11 regiments, were formed, trained in as little as two months’ time, and dispatched to service in the battlefields of the South.

During their encampment at Camp William Penn, the colored troops enjoyed a friendly relationship with many of the local residents. The late Horace Mather Lippincott, whose family homestead was adjacent to the camp, relates in at least one historical account that his grandmother baked cakes for the soldiers. Other neighbors provided campsites for the families of recruits when they came to visit.

In addition, the local citizens provided a great deal of religious influence at Camp William Penn. Rev. Robert J. Parvin of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church and many of his parishioners, including Jay Cooke, visited the camp to preach, conduct Bible classes and distribute books. The most famous preacher at the camp, however, was Lucretia Mott. As a Quaker, she was opposed to fighting of any kind, but as an abolitionist, she was deeply concerned for the welfare of the Negro troops. With her characteristic determination, she frequently stalked through the fields from her nearby home on Old York Road to visit the soldiers, and, using a large bass drum as her pulpit, she offered her religious messages.

As additional regiments were mustered in, Camp William Penn ran out of level ground on which to drill. It moved to the relatively level farmland close to City Line between Washington Lane and Sycamore Avenue and eventually extended northward from City Line to occupy farmlands of Edward M. Davis, Lucretia Mott’s son-in-law, and contiguous tracts west of Old York Road. Davis, a strong proponent of civil liberty, and Mrs. Mott, already a national figure in the anti-slavery movement, welcomed the intrusion with enthusiasm, and they both soon became absorbed in the activities of the camp.

The soldiers who went forth from Camp William Penn distinguished themselves for bravery under fire and efficiency in the campaigns in which they were employed, according to one contemporary account. Two of the 11 regiments, the 6th and the 8th, are included in “the three hundred fighting regiments,” a list selected from the entire Union force for superior fighting records, by Colonel William F. Fox. (William F. Fox – REGIMENTAL LOSSES IN THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1861-1865 – Morningside, Dayton – 595pp – errata sheet – one of the most relied upon CW reference books – source of Three Hundred Fighting Regiments – complete lists of all regiments & batteries in Union Army with losses – added chapter lists casualties in Confederate regiments)

Both regiments participated in the battle of Chaffin’s Farm, in which the 6th suffered heavy losses,and in operations incident to the siege of Petersburg.

The 8th later was engaged in the pursuit of General Robert E. Lee, and was present at the scene of the surrender at Appamattox.

The 22nd took an active part in the siege of Richmond, and was honored by its selection as one of the first Union regiments sent into Richmond. Later it escorted the casket of President Lincoln through Washington, after which it was sent to the Eastern Shore of Maryland in pursuit of the assassins.

In all, more than 1,000 of the 10,940 men trained at Camp William Penn were killed in action or died of disease. Of the various tributes to their bravery and skill, perhaps the most meaningful is the statement by Major General Benjamin F. Butler, following the charge by the 8th Regiment at Chaffin’s Farm. He wrote, “Better men were never better led, better officers never led better men. A few more such charges, and to command colored troops will be the post of honor in the American armies.”

An extremely detailed site relating to all phases of the Civil War is that of The United States Civil War Center Civil War Collections & the Civil War Book Review.

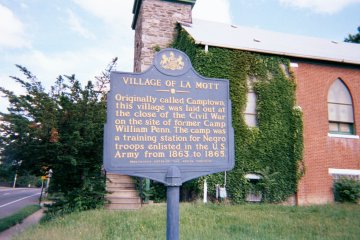

“Historical markers have been placed by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in two places in La Mott, a community that has taken its name from the first and last letters of Lucretia and the entire last name of Mott. One at the corner of Keenan Street and Cheltenham Avenue commemorates the site of Camp William Penn.

Picture of Historic marker

Another is at the entrance of Latham Park just above Willow and Sycamore Avenues on Old York Road, Honors Lucretia Mott and marks the site of her home.

There is also a stone marker in the ground at the corner of Willow and Sycamore Avenues, placed there in 1943, that describes the area as the’ Training Camp for Colored Troops 1863-1865.

A more recent ceremony has taken place in which a historic marker was installed at what has been identified as the gate to Camp William Penn.

The combination of the rich historical background that is a fabric of La Mott, its social significance and the people who live there have resulted in the certification of this community as a historic site by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in April, 1975. Not to be overlooked in the fabric of that history is the fact that Cheltenham provided many stops along the Underground Railroad.

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865.