PA…William Penn’s Colony

Individual Quakers had been emigrating to the colonies since the 1650s. Full-scale migration came in 1675 when the first full shipload of Quakers arrived and settled in West Jersey. Within six years approximately 1,400 members of the Society had emigrated there. Penn had served as a trustee of the West Jersey endeavor and his participation fed the idea of creating a colony of religious freedom. He envisioned a haven from persecution and a place where Quakers could live in harmony, “love and brotherly kindness” as an example to all Christians.

|

|

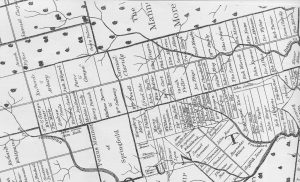

The government of England owed Penn’s father money. In lieu of payment, on June 1, 1680, Penn formerly petitioned King Charles II for a land grant west of the Delaware River between New York and Maryland. The king granted the request in 1681 with the stipulation that the new province be named in honor of Admiral Penn. Thus, the Quaker became the proprietor of Pennsylvania, an area of some 600,000 square miles (larger than the present Commonwealth of Pennsylvania…46,058 square miles (119,290 km²).

As soon as everything was settled, Penn began advertising for the sale of land tracts and sent his cousin William Markham to the colony to act as deputy governor. He instructed Markham to form a preliminary government that granted the right to vote to virtually all free inhabitants. Penn later drafted laws that promised public trials where “justice shall be neither sold, denied or delayed.” All court proceedings would be conducted in English, instead of Latin, and “in ordinary and plain character, that they may be understood.”

The Indian nations that Penn dealt with desired peace and responded positively to the Quakers and altogether the relationship was an unparalleled success. However the success did not last as settlers pushed farther west. Moreover, Penn’s relationship with the local Indians did not always carry over with the colonists. He seemed incapable of selecting suitable representatives to govern the colony, and a series of incompetent choices created friction with the province’s inhabitants and threatened Penn’s credibility and authority there. Penn’s stance on nonviolence, frequent financial straits and a boundary dispute created problems with the governor of New York and Lord Baltimore to the south.

Nor were his troubles confined to the New World. On more than one occasion Penn came dangerously close to losing his colony. This became an even greater concern with the 1685 death of Charles II and the subsequent bloodless revolution that saw the removal of Charles’ I son, the “Catholic” King James II. Three years later, James’ very Protestant daughter and Dutch son-in-law, Mary and William ascended the throne. They were not fans of Penn. Because of his friendship with James, Penn was arrested late in 1688, and again in 1691, and charged with conspiring to commit treason. He was quickly released on both occasions, but trouble in London and in Pennsylvania continued to plague him until a stroke in 1712 crippled his mind. Penn died six years later.

In 1681 Penn wrote to the Pennsylvania colonists, “You shall be governed by laws of your own making, and live a free and, if you will, a sober and industrious people. I shall not usurp the right of any, or oppress his person.” The Quaker promised, “Whatever sober and free men can reasonably desire for the security and improvement of their own happiness I shall heartily comply with…”

Penn offered the dream of a harmonious, peaceful and self-governing alternative to the raucous Cavaliers to the south and the repressive, puritanical society to the north. All the colonists had to do was live it. And they did—for eight decades. Quaker society dominated the Delaware Valley. The realty fell short of the dream, but the culture of burgeoning freedom and pluralism made a lasting impression. Many of Penn’s ideals live in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution

http://www.ushistory.org/Declaration/document

http://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/constitution.overview.html

Ref. The Quaker Migration: Allyson Patton-British Heritage pg.43-48, Jan. 2006