Preparing for Reconstruction Following the End of Fighting

The Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

What it says:

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

What it means:

In 1863, based on his war powers (see Article II, Section 2), President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation which freed the slaves held within any designated state and part of a state in rebellion against the United States. The Proclamation provided “all persons held as slaves… are, and henceforth shall be free….” Because the Proclamation did not address slaves held in Northern states, there were questions about its validity. Following the end of the fighting on February 1, 1865, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment and forwarded it to the states, It was ratified on December 18, 1865. The Thirteenth Amendment was the first of three Reconstruction era amendments (the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth) that eliminated slavery, guaranteed due process, equal protection and voting rights to all Americans.

By its adoption, Congress intended the Thirteenth Amendment to take the question of emancipation away from politics. The Supreme Court found in In Re Slaughter-House Cases, that the “word servitude is of larger meaning than slavery… and the obvious purpose was to forbid all shades and conditions of African slavery.” Although some may have questioned whether persons other than African Americans could share in the amendment’s protection, the Court held that the amendment “forbids any other kind of slavery, now or hereafter. If Mexican peonage [the practice of forcing someone to work against one’s will to pay off a debt] or the Chinese coolie labor system shall develop slavery of the Mexican or Chinese race within our territory, this amendment may safely be trusted to make it void.”

In more recent cases, the Supreme Court has defined involuntary servitude broadly to forbid work forced by the use or threat of physical restraint or injury or through law. But the Supreme Court has rejected claims that define mandatory community service, taxation, and the draft as involuntary servitude.

Ref.: The Founding Fathers and Justicelearning.org

The March Toward Reconstruction

On April 4, 1864 President Lincoln began to draw plans for Thirteenth Amendment and Reconstruction. When submitted to the House of Representatives in June of 1864. Lincoln wanted have some action in early 1865, before the newly elected members of the election of 1864 took office.

In January of 1865 the subject was again raised. In the interim some Democrats changed their votes. On the morning of January 31st, 1865 a vote was taken and the measure passed by a 119 to 56 margin. In celebration the Congress adjourned for the remainder of the day.

New Jersey, Kentucky and Delaware did not ratify the amendment at the time. Later Tennessee and Louisiana voted to ratify the amendment. It took the votes of former Confederate states to provide the 3/4s needed for approval. Kentucky remained a holdout until

Before the official ratification of the Amendment there were early signs of change. On November 1st, 1864 Maryland voted to abolish slavery. On January 11, 1865 Missouri also abolished slavery. On March 3rd of that year all wives and children of black soldiers who were serving with the U.S.C.T. were freed. Also, in that year the first social event that hosted blacks in the White House was held. The repeal of a 1810 law forbidding blacks to carry the mail was enacted.

Many other “Black Laws” were repealed during the period and in a landmark occasion John Rock was admitted as a lawyer to appear before the Supreme Court. One of the ‘Black Laws” repealed now gave Black people the right to testify in federal courts.

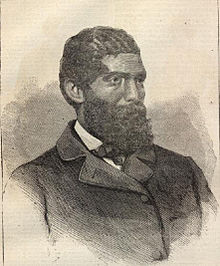

John Rock (1825 – 1866)

The first African American to be admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court, was a teacher, a physician, a lawyer, and a freedom-fighter.

With a burning desire to learn, John Rock was destined to become one of the most educated people of his day. He was born of free parents in Salem, New Jersey on October 13, 1825, in a time when few whites finished grammar school and it was illegal in many states for African Americans to learn to read. He was a studious child, and even though his parents were of modest means, they encouraged him and provided for his formal education.

In 1844, at the age of 19, he had completed sufficient schooling to become a teacher. Teaching in a one-room school in Salem, his work was impressive, and the praise given him by veteran teachers caught the attention of two local doctors. In 1848, they loaned Rock their books so he could study dentistry. A tireless worker, he would teach school for six hours, tutor private students for two hours, and then study dentistry for eight hours each day.

In 1850, Rock opened a dental office in Philadelphia and a year later won a silver medal for his work. In 1852, he began attending lectures at the American Medical College and, at the age of 27, was one of the first African Americans to receive a medical degree. Devoted to the abolitionist cause, Rock was known for his inspiring public speeches, but he found himself increasingly frustrated by the laws of his day. In 1860, he gave up his medical practice and moved to Boston to study law.

His decision to become a lawyer occurred soon after one of the most infamous rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court, known as the Dred Scott decision. Dred Scott (1795?-1858) was a slave who had sued for his liberty after spending four years with his master in a territory where slavery was banned by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The resulting decision by the U.S. Supreme Court on March 7, 1857, declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, essentially denying that African Americans have any rights and sanctioning their continued oppression.

As a legal scholar, Rock distinguished himself and was sponsored by a white lawyer before the Superior Court of Massachusetts in Boston on September 14, 1861. He passed his examinations with ease and was admitted the same day to practice in all the courts of Massachusetts. He soon opened an office in Boston and became a justice of the peace.

As the Civil War began in 1861, Rock intensified his efforts to fight for racial equality. In his speeches, he demanded the same “equal opportunities and equal rights our brave men are fighting for.” He successfully lobbied Congress to get equal pay for black troops. The first African American to be received on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, Rock was on his way home to Boston when he was arrested at the Washington, D.C. railroad station for not having the pass that blacks were often required to carry. The incident allegedly prompted U.S. Representative James Abram Garfield, who later became president, to abolish the use of passes for black people.

In 1864, Rock wrote to Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts requesting his help in becoming admitted to practice before the U.S. Supreme Court. Senator Sumner replied that nothing could be done as long as Roger B. Taney, who wrote the Dred Scott decision, was still chief justice. When Taney died, Lincoln replaced him with an abolitionist, Salmon P. Chase.

On February 1, 1865, Congress approved the 13th Amendment ending slavery. Soon afterwards, Rock was ushered into the U.S. Supreme Court and took the oath admitting him to that court. A reporter for the New York Times dramatically described the scene as the African American lawyer stood, in the monarchial power of recognized American Manhood and American Citizenship, within the bar of the court which had [just eight years earlier] solemnly pronounced that black men had no rights which white men were bound to respect; stood there a recognized member of it, professionally the brother of the distinguished counselors on its long rolls, in rights their equal, in the standing which rank gives their peer. By Jupiter, the sight was grand.

John Rock died on December 3, 1866, just a few months before Congress would pass the Civil Rights Act of 1867, the first law to embody the rights for which he had struggled so long. A Freemason, he was buried with full Masonic honors at the age of 41.

Acknowledgements:

Permission to use the above image of John Rock was granted by:

Photographs and Prints Division

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

The New York Public Library

Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

This image first appeared in Harpers Weekly, February 25, 1864, p. 124. Photo of John H. Rock. Wood engravings. [photographer credit: Richards, Philadelphia]

This story about John Rock is based on an article by Richard L. Nygaard, a judge of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. The article appeared originally in the journal Experience and was reprinted in the ABA publication Law Day Stories. Other sources include Black Facts Online and the National Park Service Boston African American National Historic Site.